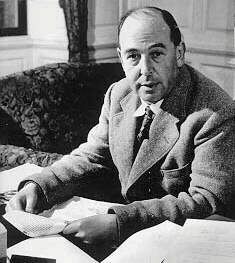

C.S. Lewis and Francis Schaeffer--they were the mother milk of the evangelical renewal among the college students of the 1970s and 1980s. This unlikely pair were used by God to bless us far beyond their imagination. This is from the current Saturday Evening Post.

In living colour

“You are never too old to set another goal or to dream a new dream.”—C. S. Lewis

A new generation of Americans is rediscovering C.S. Lewis through the box office hit The Chronicle of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe.

Published: March/April 2006

The work of Clive “Jack” Staples Lewis as a Christian apologist and a Christian writer is well accepted across the denominational spectrum. More than 50 books have been published to his credit, among them Mere Christianity, The Problem of Pain, Christian Behavior, and Surprised by Joy. Annual book sales remain over two million—half of which comes from The Chronicles of Narnia, perhaps the greatest classic of children’s literature of the 20th century.

However, Lewis’s greatest achievement was not in academia, but in the university of life. In a time when modern Western civilization was entering the post-Christian era, Lewis dared to challenge the minds behind modernism and liberal theology.

David Barratt, author of C.S. Lewis and His World (Eerdmans, 1987), says Lewis’s finest achievement was the ability “to bring old truth and give it new relevancy and vitality in a secular age, and to challenge the new complacencies.” Orthodox Christianity was on the retreat at the time of Lewis’s conversion—undermined by other liberal theology and scientific and secular skepticism.

“At his death,” writes Barratt, “the Christian Church in the United Kingdom, and even more so in the United States, was entering renewal, with Christians emerging from their ghetto with new confidence and hope. Lewis’s impact must be acknowledged in this.”

Born in Belfast, Ireland, in 1898, C. S. Lewis was one of two sons of Albert and Flora Lewis. His mother died of cancer when he was 10. His father, feeling the weight of her death, placed Lewis in a boarding school where he joined his older brother, Warren, affectionately called Warnie. Both boys endured horrendous conditions at the school, where the headmaster was prone to fits of rage. It was there Lewis began to pray and read his Bible. After the school closed, Lewis entered Malvern Cherbourg School in England and later Malvern College. Once again the negative effects of public school were great. And after asking to be removed from the school, Lewis was placed under the instructional care of W. T. Kirkpatrick, whom Lewis called “a hard satirical atheist.”

Kirkpatrick saw strong potential in Lewis and informed Albert Lewis that his son could be a writer or a scholar, “but you’ll not make anything else of him.” Realizing Kirkpatrick’s assessment was true, Lewis applied for and received a scholarship to University College, the oldest of the Oxford colleges. Soon after he entered the university, Lewis volunteered for service in World War I. He was allowed to remain at Oxford until commissioned and sent off to fight in the trenches of northern France.

Memories from Lewis’s childhood reveal a deep desire for joy. As a child he imagined places where joy existed freely and eternally. As an adult he read Plato, the Romantic poets, and Norse Germanic mythologies in hopes of finding a sense of lasting joy. “I doubt whether anyone who has tasted [joy] would ever, if both were in his power, exchange it for all the pleasures in the world,” wrote Lewis.

After being wounded and discharged, Lewis resumed his studies, where he graduated at the top of his class. With no philosophy teaching posts available, Lewis entered a fourth year at Oxford College, where he met a Christian student named Nevill Coghill, a man whose perspective helped to change the way Lewis viewed life.

Lewis began reading the works of Christian authors. He particularly admired George Macdonald, a Scottish Christian writer; in his writings, Lewis found a quality of holiness he had not seen before. The works of John Milton, especially Paradise Lost, intrigued him, as did the close friendship he shared with J. R. R. Tolkien.

In 1925, Lewis received an English fellowship at Magdalen College at Oxford. Lewis’s classes were filled to capacity, so much so that a larger lecture hall had to be found. Meanwhile, his search for God accelerated. He had moved from idealism to pantheism and then to theism.

“In the Trinity Term of 1929 I gave in, and admitted that God was God, and knelt and prayed. The hardness of God is kinder than the softness of men, and His compulsion is our liberation.” Lewis’s final step toward Christianity came when he accepted the incarnation of Jesus Christ as fact. “I was now approaching the source from which those arrows of Joy had been shot at me ever since childhood. No slightest hint was vouchsafed me that there ever had been or ever would be any connection between God and Joy. If anything, it was the reverse. I had hoped that the heart of reality might be of such a kind that we can best symbolize it as a place; instead, I found it to be a Person.”

Eternal joy became a reality for C. S. Lewis.

Source: http://www.satevepost.org/issues/2006/0304/73701051.shtml

1 comment:

While I am glad that C. S. Lewis's name and writings continue to get notice, I was struck by this article's mistakes. Claiming that Jack 'began to pray and read his Bible' in boarding school leaves a false impression that he was moving towards faith at that time.

But the real howler is talking about how 'his search for God accelerated.' As he plainly says in 'Surprised by Joy,' you might as well speak of a mouses' search for a cat. It was God's relentless search for him.

<>< Ron Troup

rltroup@netzero.net

Post a Comment