It's easy to spot the main sources for the writer of this article: they weren't the Biblical conservatives--either in the SBC or the majority dissenters in the ABCUSA. They--we--are Neanderthal dummies, don't you know? Meanwhile, the ABC, incarnated here in the form of the rotting hulk of the great First Baptist Church in Amercia, totters on, the True Standard-Bearer. Give me a break...

In birthplace of Baptist church, strains show among followers

By Ray Henry, Associated Press Writer January 21, 2006

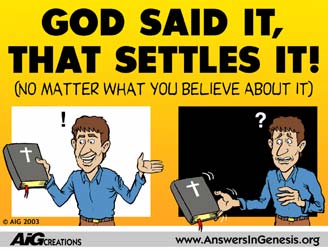

PROVIDENCE, R.I. --Grace Harbor Community Church's young congregants meet in a crowded hotel conference room, learn scripture via PowerPoint and listen to a "praise team" play bongo drums. The Web site of the 4-year-old Southern Baptist church includes a cartoon proclaiming "God said it, that settles it!"

Less than a mile away, the graying worshippers at First Baptist Church in America prefer Bach to bongos, listen to a black-robed minister who quotes Winston Churchill and meet in a white-steepled National Historic Landmark.

First Baptist's historic congregation planted the faith in America, where 30 million people now call themselves Baptist. But in the movement's birthplace of Rhode Island, just over two percent of people are Baptist and some of its earliest churches have struggled to maintain their memberships. Meanwhile, Southern Baptist churches like Grace Harbor are the dominant face of the faith -- which has evolved to become far more conservative than the church's roots in liberal Rhode Island would suggest.

Most Baptist factions trace their roots to Roger Williams, the 17th-century minister who founded Rhode Island and organized the nation's first Baptist congregation in 1638. The uncompromising provocateur was banished from Massachusetts for attacking state-sponsored Puritan congregations, demanding the separation of church and state and arguing that American Indians had property rights.

Williams was fiercely committed to what he called "soul freedom" -- or freedom of religion. Just months after organizing the first Baptist congregation, he left it and rejected the institutional church altogether.

Williams said he had a "restless unsatisfiedness" in his soul, and one of his contemporary critics called him "constant only in his inconstancy." Scholars say those attributes continue to mark the faith today.

"Wherever two or three Baptists are gathered together, there's a schism," said J. Stanley Lemons, the First Baptist church historian.

Over the centuries, Baptists have split into three major branches: the American Baptist Churches in the U.S.A., the Southern Baptist Convention and the National Baptists, mostly black congregations with diverse beliefs. Dozen of smaller groups populate the Baptist family tree, according to Pam Durso, the associate director of The Baptist History and Heritage Society in Brentwood, Tenn.

The largest denomination by far is the Southern Baptists, which split from the American Baptists in 1845 after delegates meeting in Providence banned slaveholders from serving as missionaries. Once confined to the south, the denomination spread north during the 20th century and claims 16.4 million members, making it the nation's single largest Protestant church.

Williams' old congregation remains American Baptist, which has just 1.8 million followers and is concentrated in the north, according to the American Religion Data Archive.

The different groups subscribe to many of the same beliefs. They only baptize adults who are "born again" in their faith, and hold that the Bible is their sole source of authority. They recognize the autonomy of local churches from religious hierarchies.

But they differ widely on a host of social and political views. Southern Baptists ban women from serving as pastors. Their official "Baptist Faith and Message" calls on a wife to "submit" to her husband's leadership, although it calls both sexes equal before God.

While some American Baptist pastors say gays can be good Christians, Southern Baptists denounce gay marriage and have pulled out of an alliance that included gay friendly churches. Former Southern Baptist President Paige Patterson said he and most of the denomination's top leadership is Republican.

Those stances can be a turn-off for churchgoers in Providence, a Blue State capitol run by an openly gay mayor, said Evan Howard, pastor of Community Church of Providence, formerly Central Baptist Church.

The 200-year-old American Baptist congregation changed its name two years ago -- in part because Howard realized his neighborhood could no longer support a traditional Baptist church, and in part because church members feared the term "Baptist" would deter newcomers who associate it with Southern Baptists who hold views they dislike.

"We're not comfortable with that sort of black and white feeling. We're more comfortable saying all welcome," he said.

But he recognizes that other Baptists would spurn his teachings, such as that parts of the Bible should be read metaphorically, rather than literally.

"The Southerners would say 'This guy's not Christian, how could he even be a minister?'" he said.

Some Baptists complain that conservatives are the face of the faith. Among the critics is Walter Shurden, the executive director of the Center for Baptist Studies at Mercer University in Macon, Ga., who left the Southern Baptist church because he felt it strayed too far from Williams' teachings.

"Do we follow the vision of Roger Williams that affirms this role of freedom, or do we become Baptists who try to conform everyone into our image?" he asked.

Andy Haynes, pastor of Grace Harbor, says it's not his goal to create division. He says he's had a friendly reception from Rhode Islanders, though his church, aimed at a college-aged crowd, doesn't always see eye-to-eye with its founding congregation.

"We have our differences," Haynes said.

Lemons, the First Baptist historian, is more blunt about the split. He says it upsets him to hear famous Baptist pundits like Pat Robertson, an independent Baptist minister, say God will forsake those who oppose teaching "intelligent design" in public schools.

Lemons wonders whether Roger Williams -- the first backer of church-state separation -- would embrace Baptists like Robertson.

"For these guys to talk about a Christian nation," he said, "Williams would go up in smoke."

No comments:

Post a Comment